6. Viral hepatitis and HIV coinfection

6.1 Management of HBV/HIV coinfection

Stefan Mauss, Kathrin van Bremen

Abstract

HBV/HIV-coinfection represents the most frequent viral coinfection in people living with HIV (PLWH). About 2.7 million (7.4%) PLWH are thought to be HBV-coinfected. Due to the mutual interference of HBV and HIV-coinfection, fibrosis progression, liver cirrhosis, risk of development of hepatocellular carcinoma and overall liver-disease related death is increased. Therefore, every PLWH with chronic HBV-coinfection needs an HBV-active drug as part of their antiretroviral treatment (ART) with the overall goal of HBV-DNA suppression. Functional cure with loss of HBs-Ag is a rare but possible event particularly after initiation of antiretroviral therapy as part of an immune reconstitution phenomenon.

Introduction

The prevalence and transmission routes of HBV coinfection in the HIV+ population vary substantially by geographic region (Alter 2006, Konopnicki 2005). Globally, 7, 4% of the 37 Mio PLWH are estimated to be coinfected with HBV (WHO 2021). In the United States and Europe, the majority of HIV positive men who have sex with men (MSM) have evidence of past HBV infection, and 5–10% show persistence of HBs- antigen, with or without replicative hepatitis B as defined by the presence of HBV DNA (Konopnicki 2005). Overall, rates of HBV/HIV coinfection are slightly lower among intravenous drug users compared to MSM and much lower among people infected through heterosexual contact (Núñez 2005).

In endemic regions of Africa and Asia, the majority of HBV infections are transmitted vertically at birth or before the age of 5 through close contact within households, medical procedures and traditional scarification (Modi 2007). The prevalence among youth in most Asian countries has substantially decreased since the introduction of vaccination on nationwide scales (Shepard 2006). In Europe, vaccination of children and members of risk groups is promoted and reimbursed by health care systems in most countries.

The natural history of hepatitis B is altered by simultaneous infection with HIV. Immune control of HBV is negatively affected leading to a reduction of HBs-antigen seroconversion. If HBV persists, the HBV DNA levels are generally higher in HIV positive patients not on antiretroviral therapy (Bodsworth 1989, Bodsworth 1991, Hadler 1991). In addition, with progression of cellular immune deficiency, reactivation of HBV replication despite previous HBs-antigen seroconversion may occur (Soriano 2005). However, after immune recovery due to antiretroviral therapy, HBe-antigen and HBs-antigen seroconversion occur in a higher proportion of patients compared to HBV monoinfected patients (up to 18%) treated for chronic hepatitis B (Schmutz 2006, Piroth 2010, Kosi 2012, van Bremen 2020).

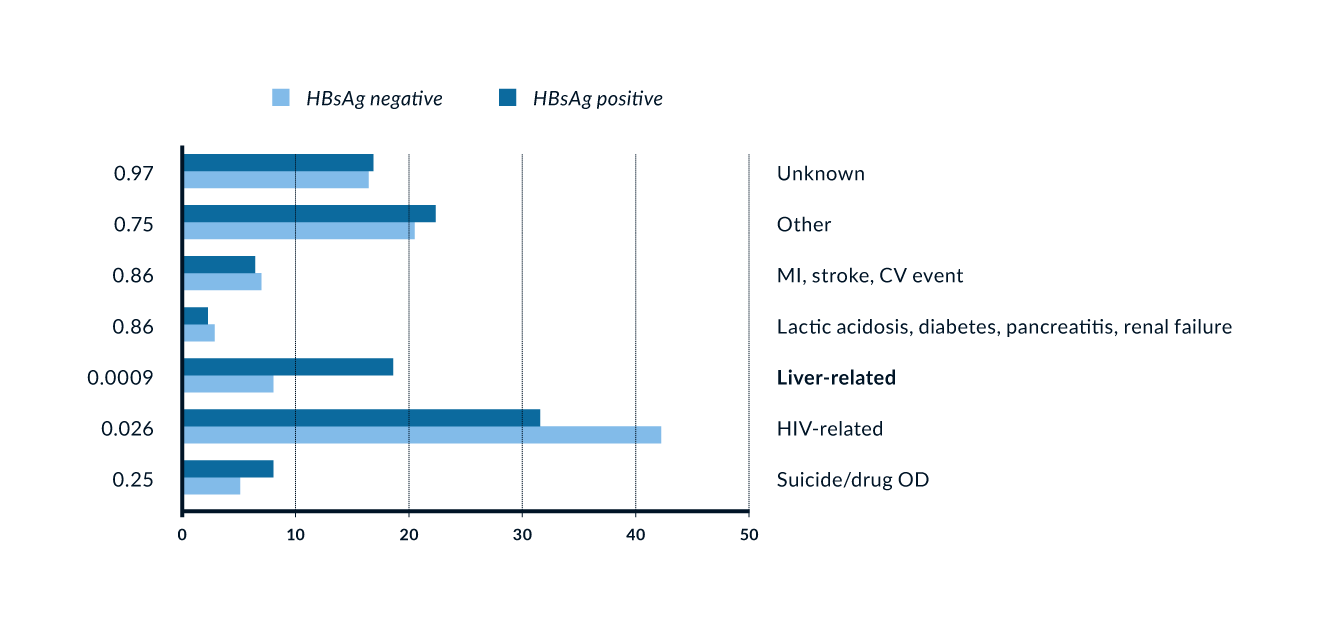

In untreated HIV infection, faster progression to liver cirrhosis is reported for HBV/HIV-coinfected patients (Puoti 2006). Moreover, hepatocellular carcinoma may develop at an earlier age and is more aggressive in this population (Puoti 2004, Brau 2007). Moreover, persisting HBV-DNA >200 IU/L presents a risk factor in PLWH (Kim 2021). Start of HBV suppressive treatment with tenofovir at early age (<46 years) was found to be associated with a lower HCC incidence (Wandeler 2021).Being HBV-coinfected results in increased mortality for HIV positiveindividuals, even after the introduction of effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), as demonstrated by an analysis of the EuroSIDA Study, which shows a 3.6-fold higher risk of liver-related deaths among HBsAg positive patients compared to HBsAg negative individuals (Konopnicki 2005, Nikolopoulos 2009 (Figure 1). In the UK Collaborative HIV cohort a 10-fold increased risk of liver-related mortality was seen among HBV/HIV- coinfected compared to HIV-monoinfected individuals, particularly among individuals with low CD4+ cell counts (Thornton 2017). Therefore, early treatment and screening for complications of liver disease in HBV/HIV-coinfected patients especially for HCC remains crucial.

The beneficial impact of treatment of HBV in HBV/HIV coinfection was first demonstrated by data from a large cohort showing a reduction in mortality with lamivudine treatment compared to untreated patients (Puoti 2007). This result is even more remarkable because lamivudine is the least effective HBV polymerase inhibitor due to the rapid development of drug resistance. In general, because of its limited long-term efficacy, lamivudine monotherapy cannot be considered as appropriate therapy for either mono HBV infection or HBV/HIV coinfection (Matthews 2011).

In addition, two large cohort studies (EuroSIDA and MACS) plus data from HBV monoinfection studies showing a reduction in morbidity and mortality established the need to treat chronic hepatitis B in HBV/HIV- coinfected patients as early as possible.

Treatment of chronic hepatitis B in HBV/HIV- coinfected patients on antiretroviral therapy

As antiretroviral therapy is recommended for all HIV patients independent of CD4-count to reduce HIV-associated morbidity and mortality and to prevent HIV transmission, all HBV/HIV-coinfected patients are considered eligible for antiretroviral therapy by current guidelines (e. g. EACS 2022). A TDF/TAF-containing regimen is now recommended in all HBV/HIV-coinfected patients. The previous complicated recommendations for how to treat chronic hepatitis B in patients without antiretroviral therapy are obsolete. As antiretroviral drugs that are also active against HBV can usually be used, interferon- based treatment of HBV is not indicated. Data in the literature for HIV-coinfected patients on interferon therapy for HBV infection are limited and not very encouraging (Núñez 2003). In addition, treatment studies intensifying TDF therapy with pegylated interferon for one year showed no increase in HBV seroconversion rates (Boyd 2016).

In general, tenofovir based therapy is the standard of care for HBV in HIV-coinfected patients, because of its strong HBV polymerase activity and antiretroviral efficacy. Tenofovir has been a stable and effective therapy in the vast majority of treated HBV/HIV-coinfected patients (van Bömmel 2004, Mathews 2009, Martin-Carbonero 2011, Thibaut 2011). Its antiviral efficacy is not impaired in HBV/HIV-coinfected compared to HBV-monoinfected patients (Plaza 2013). No conclusive pattern of resistance mutations has been identified in studies or cohorts (Snow-Lampart 2011). These data are still valid in 2023. In theory, resistance may occur in patients on long-term therapy, as with any other antivirals. Because of that, when choosing an HBV polymerase inhibitor, complete suppression of HBV DNA is important to avoid the development of HBV drug resistance.

In HBV treatment naïve patients, a combination of tenofovir (either TAF or TDF) plus lamivudine/emtricitabine to treat both infections is usually recommended. Even for patients who harbour lamivudine-, telbivudine- or adefovir-resistant HBV due to previous therapies this strategy proves to work very well. As adefovir and telbivudine are no longer available and obsolete to use HBV-relevant resistance against these antivirals will no longer be relevant.

Initiating ART including tenofovir resulted in higher rates of HBe antigen loss and seroconversion as expected from HBV-monoinfected patients (Schmutz 2006, Piroth 2010, Kosi 2012, van Bremen 2020). This may be due to the additional effect of immune reconstitution in HBV/HIV coinfected patients improving immunological control of HBV replication.

For patients with advanced liver fibrosis or liver cirrhosis a maximally active continuous HBV polymerase inhibitor therapy is important to avoid further fibrosis progression and hepatic decompensation and to reduce the risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma. Tenofovir plus lamivudine/emtricitabine is the treatment of choice. If the results are not fully suppressive, adding entecavir should be considered (Ratcliffe 2011). A reduction in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma has been shown for patients on HBV polymerase inhibitors compared to untreated patients, strengthening the antiproliferative effects of suppressive antiviral therapy (Hosaka 2012).

Liver ultrasound or an alternative imaging procedure is indicated at least every six months in patients with liver cirrhosis irrespective of HBV-DNA suppression as well as in non-cirrhotic patients with risk factors (family history of HCC, Asian/Africans patients, HDV-coinfection, age>45 years) for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. In patients with advanced cirrhosis, esophagogastroscopy should be performed as screening for oesophageal varices. For patients with hepatic decompensation and full treatment options for HBV and who have stable HIV infection, liver transplantation should be considered as posttransplant life expectancy seems to be the same as for HBV-monoinfected patients (Coffin 2007, Tateo 2009). Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma may also be considered liver transplant candidates, PLWH showed similar rates concerning recurrence and disease free survival vs. patients without HIV-infection. (Eman 2019).

The acquisition of adefovir resistance mutations from the past as well as multiple lamivudine resistance mutations may impair the activity of tenofovir (Fung 2005, Lada 2012, van Bömmel 2010), although even in these situations tenofovir retains sufficient activity against HBV (Berg 2010, Patterson 2011, Petersen 2012).

In lamivudine-resistant HBV the antiviral efficacy of entecavir in HIV- coinfected patients is reduced, as it is in HBV monoinfection (Shermann 2008). Because of this and the property of tenofovir as a fully active antiretroviral, tenofovir-disoproxilfumarate or tenofovir-alafenamide is the preferred choice in treatment-naïve HBV/ HIV coinfected patients who will use ART. The use of entecavir as an add-on to tenofovir or other drugs in the case of not fully suppressive antiviral HBV therapy has not yet been studied in HBV/HIV coinfection. This decision should be made on a case-by-case basis.

Based on history of antiretroviral therapy, combination HBV therapy of tenofovir plus lamivudine/emtricitabine was expected to be superior to tenofovir monotherapy, in particular in patients with highly replicative HBV infection. However, this hypothesis has not as yet been supported by studies (Schmutz 2006, Mathews 2008, Mathews 2009, Price 2013). However, there are data showing better viral suppression for entecavir and tenofovir-DF compared to entecavir monotherapy in highly replicative patients with HBV-monoinfection, but no such a study is available for a comparison with tenofovir monotherapy (Lok 2012).

In the case of HIV resistance to tenofovir, it is usually important to continue using tenofovir for HBV activity when switching to other antiretrovirals. Discontinuation of the HBV polymerase inhibitor without maintaining the antiviral pressure on HBV can lead to necroinflammatory flares that can result in acute liver decompensation, particularly in patients with liver cirrhosis. Therefore, life-long treatment with HBV-active drugs are recommended.

Nowadays, two-drug regimens (2DR) without TDF have become more frequent. 2DR are not recommended in HBV/HIV-coinfected patients as HBV suppression needs to be maintained at any time to prevent further related morbidity and mortality.

In 2015, tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) was approved as antiretroviral therapy in Europe and the US. TAF is a new formulation of tenofovir with lower plasma exposure of the active drug tenofovir compared to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF). TAF may offer advantages concerning long term toxicities involving bone and kidney over TDF (Agarwal 2015, Sax 2015). TAF can substitute TDF as HBV therapy in HBV/HIV-coinfected patients (Gallant 2016). The ALLIANCE study has shown a higher rate of maximal HBV-DNA suppression on TAF- vs. TDF-based therapy (B/F/TAF 63.0% vs. DTG+F/TDF 43.4%) in PLWH with recent ART-initiation at week 48. However, no breakthroughs or treatment failures were observed under TDF therapy compared to TAF. Interestingly, rate of HBsAg-loss was higher when using TAF-based therapy (12.6% vs. 5.8%) (Avihingsanon 2022Clinical consequences of these preliminary findings seem limited.

The potentially nephrotoxic effect of TDF is a concern. Although nephrotoxicity is rarely observed in HIV negative patients treated with TDF monotherapy (Heathcote 2011, Mauss 2011), renal impairment has been more frequently reported in HIV positive patients using TDF as a component in ART and may be associated in particular with the combined use of TDF and ritonavir-boosted HIV protease inhibitors (Mauss 2005, Fux 2007, Goicoecha 2008, Mocroft 2010). In addition, the approved cytochrome P450 3A inhibitor cobicistat can also increase creatinine levels. Regular monitoring of renal function in HBV/HIV-coinfected patients including estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and assessment of proteinuria is necessary. In the case of a reduced eGFR, TDF should be substituted by TAF or should be dosed at a reduced frequency according to the label. In the case of significant proteinuria, TDF should also be replaced by TAF. Alternatively in specific situations in the case of tenofovir associated nephrotoxicity tenofovir can also be replaced by entecavir.

Conclusion

For HBV/HIV coinfected patients, antiretroviral therapy is indicated to treat both infections simultaneously. Therefore, HBV treatment of choice is tenofovir-based therapy. Due to rapid development of resistance when HBV is not fully suppressed HBV monotherapy with either lamivudine or emtricitabine should not be considered. A combination of tenofovir plus lamivudine or emtricitabine as a primary combination therapy has theoretical advantages over tenofovir alone, but studies supporting this concept have not been published to date. However, as tenofovir is combined with emtricitabine or lamivudine in most antiretroviral regimen this seems to be a more theoretical argument and not reflected by reality.

In general, treatment of HBV as a viral disease follows the same rules as HIV therapy, aiming at full suppression of the replication of the virus to avoid the development of resistance. Successful viral suppression of hepatitis B results in inhibition of necroinflammatory activity, reversion of fibrosis, and most importantly a decrease in the incidence of hepatic decompensation and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Key messages

- HBV/HIV-coinfection leads to increased liver and overall mortality rates

- Screening of HBV-coinfection in every PLWH is guideline recommended

- Vaccinate PLWH without HBV-seroprotection

- TDF/TAF-containing ART is recommend in every PLWH with HBV-coinfection

- HCC-screening recommended every 6 months in cirrhotic patients and non-cirrhotic patients with risk factors

- Functional cure with HBsAg loss rare but possible event

Figure 1. Association of HBV/HIV coinfection and mortality (Konopnicki 2005). More than one cause of death allowed per patient; p-values from chi-squared tests.

Figure 1. Association of HBV/HIV coinfection and mortality (Konopnicki 2005). More than one cause of death allowed per patient; p-values from chi-squared tests.

References

Alter M. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J Hepatol 2006; 44:6-9.

Agarwal K, Fung SK, Nguyen TT, et al. Twenty-eight day safety, antiviral activity, and pharmacokinetics of tenofovir alafenamide for treatment of chronic hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol. 2015;62(3):533-40.

Avihingsanon A, Lu H, Leong CL, et al. Week 48 of a phase 3 randomised controlled trial of bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (B/F/TAF) vs dolutegravir + emtricitabine/ tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (DTG+F/TDF) as initial treatment in HIV/HBV-coinfected adults (ALLIANCE). AIDS 2022, July 29-August 2, Montreal. Abstract OALBX0105

Berg T, Marcellin P, Zoulim F, et al. Tenofovir is effective alone or with emtricitabine in adefovir-treated patients with chronic-hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology 2010;139:1207-17.

Bodsworth N, Donovan B, Nightingale BN. The effect of concurrent human immunodeficiency virus infection on chronic hepatitis B: a study of 150 homosexual men. J Infect Dis 1989;160:577-82.

Bodsworth NJ, Cooper DA, Donovan B. The influence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection on the development of the hepatitis B virus carrier state. J Infect Dis 1991;163:1138-40.

Boyd A, Piroth L, Maylin S, et al. Intensification with pegylated interferon during treatment with tenofovir in HIV-hepatitis B virus co-infected patients. J Viral Hepat. 2016;23(12):1017-1026.

Brau N, Fox R, Xiao P, et al. Presentation and outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma in HIV-infected patients: A US-Canadian multicenter study. J Hepatol 2007;47:527-37.

Chan HL, Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, et al. Treatment of Hepatitis B e Antigen-Positive Chronic Hepatitis with Telbivudine or Adefovir: A Randomised Trial. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:2-11.

Coffin CS, Stock PG, Dove LM, et al. Virologic and clinical outcomes of hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-HBV coinfected transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2010;10:1268-75.

Crowell TA, Gebo KA, Balagopal A, et al. Impact of hepatitis coinfection on hospitalisation rates and causes in a multicenter cohort of persons living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(4):429-37.

EACS guidelines 2022 Version 11.1. http://www.eacsociety.org/guidelines/eacs-guidelines/eacs-guidelines.html

Eman P, Chacon E, Gupta M et al. Long term outcomes of patients transplanted for hepatocellular carcinoma with human immunodeficiency virus infection. HPB (Oxford). 2019 (8):1009-1016

Fung SK, Andreone P, Han SH, et al. Adefovir-resistant hepatitis B can be associated with viral rebound and hepatic decompensation. J Hepatol 2005;43:937-43.

Fux CA, Simcock M, Wolbers M, et al. Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Tenofovir use is associated with a reduction in calculated glomerular filtration rates in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Antivir Ther 2007;12:1165-73.

Gallant J, Brunetta J, Crofoot G, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Switching to a Single-Tablet Regimen of Elvitegravir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/ Tenofovir Alafenamide in HIV-1/Hepatitis B-Coinfected Adults. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(3):294-298.

Goicoechea M, Liu S, Best B, et al. California Collaborative Treatment Group 578 Team. Greater tenofovir-associated renal function decline with protease inhibitor-based versus nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor-based therapy. J Infect Dis 2008;197:102-8.

Hadler SC, Judson FN, O’Malley PM, et al. Outcome of hepatitis B virus infection in homosexual men and its relation to prior human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis 1991;163:454-9.

Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, Buti M, et al. Three-year efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 2011;140:132-43.

Hosaka T, Suzuki F, Kobayashi M, et al. Long-term entecavir treatment reduces hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2012.

Kim N, Newcomb C, Carbonari C et al. Risk of HCC With Hepatitis B Viraemia Among HIV/HBV-Coinfected Persons in North America. Hepatology 2021; 74(3):1190-1202

Konopnicki D, Mocroft A, de Wit S, et al. Hepatitis B and HIV: prevalence, AIDS progression, response to highly active antiretroviral therapy and increased mortality in the EuroSIDA cohort. AIDS 2005;19:593-601.

Kosi L, Reiberger T, Payer BA, et al. Five-year on-treatment efficacy of lamivudine-, tenofovir- and tenofovir + emtricitabine-based HAART in HBV-HIV-coinfected patients. J Viral Hepat. 2012, 19(11):801-10.

Lada O, Gervais A, Branger M, et al. Quasispecies analysis and in vitro susceptibility of HBV strains isolated from HIV-HBV-coinfected patients with delayed response to tenofovir. Antivir Ther. 2012;17(1):61-70.

Lampertico P, Viganò M, Manenti E, Iavarone M, Sablon E, Colombo M. Low resistance to adefovir combined with Lamivudine: a 3-year study of 145 Lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B patients. Gastroenterology 2007;133:1445-51.

Lin K, Karwowska S, Lam E, Limoli K, Evans TG, Avila C. Telbivudine exhibits no inhibitory activity against HIV-1 clinical isolates in vitro.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010;54:2670-3.

Lok AS, Trinh H, Carosi G, et al. Efficacy of entecavir with or without tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for nucleos(t)ide-naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(3):619-28.

Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J, et al. Clinical and virological outcomes in HIV-infected patients with chronic hepatitis B on long-term nucleos(t)ide analogues. AIDS 2011;25:73-9.

Matthews GV, Avihingsanon A, Lewin SR, et al. A randomised trial of combination hepatitis B therapy in HIV/HBV coinfected antiretroviral naïve individuals in Thailand. Hepatology 2008;48:1062-9.

Matthews GV, Seaberg E, Dore GJ, et al. Combination HBV therapy is linked to greater HBV DNA suppression in a cohort of lamivudine- experienced HIV/HBV coinfected individuals. AIDS 2009;23:1707-15.

Matthews GV, Manzini P, Hu Z, et al. Impact of lamivudine on HIV and hepatitis B virus-related outcomes in HIV/hepatitis B virus individuals in a randomised clinical trial of antiretroviral therapy in southern Africa. AIDS 2011;25:1727-35.

Mauss S, Berger F, Schmutz G. Antiretroviral therapy with tenofovir is associated with mild renal dysfunction. AIDS 2005;19:93-5.

Mauss S, Berger F, Filmann N, et al. Effect of HBV polymerase inhibitors on renal function in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 2011;55:1235-40.

Mocroft A, Kirk O, Reiss P, et al. Estimated glomerular filtration rate, chronic kidney disease and antiretroviral drug use in HIV positive patients. AIDS. 2010;24(11):1667-78.

Modi A, Feld J. Viral hepatitis and HIV in Africa. AIDS Rev 2007;9:25-39.

Núñez M, Puoti M, Camino N, Soriano V. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B in the human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient: present and future. Clin Infect Dis 2003;37:1678-85.

Nikolopoulos GK, Paraskevis D, Hatzitheodorou E, et al. Impact of hepatitis B virus infection on the progression of AIDS and mortality in HIV-infected individuals: a cohort study and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48:1763-71.

Núñez M, Soriano V. Management of patients co-infected with hepatitis B virus and HIV. Lancet Infect Dis 2005;5:374-82.

Patterson SJ, George J, Strasser SI, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate rescue therapy following failure of both lamivudine and adefovir dipivoxil in chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 2011;60:247-54.

Petersen J, Ratziu V, Buti M, et al. Entecavir plus tenofovir combination as rescue therapy in pre-treated chronic hepatitis B patients: An international multicenter cohort study. J Hepatol 2012;56(3):520-6.

Piroth L, Pol S, Lacombe K, Miailhes P, et al. Management and treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in HIV positive and negative patients: the EPIB 2008 study. J Hepatol 2010;53:1006-12.

Plaza Z, Aguilera A, Mena A, et al. Influence of HIV infection on response to tenofovir in patients with chronic hepatitis B. AIDS.2013;27(14):2219-24.

Price H, Dunn D, Pillay D, et al. Suppression of HBV by tenofovir in HBV/HIV coinfected patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis.PLoS One. 2013;8(7): e68152.

Puoti M, Bruno R, Soriano V, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in HIV-infected patients: epidemiological features, clinical presentation and outcome. AIDS 2004;18:2285-93.

Puoti M, Cozzi-Lepri A, Arici C, et al. Impact of lamivudine on the risk of liver-related death in 2, 041 HBsAg- and HIV positive individuals: results from an inter-cohort analysis. Antivir Ther 2006;11:567-74.

Puoti M, Torti C, Bruno R. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B in co-infected patients. J Hepatol 2006;44:65-70.

Ratcliffe L, Beadsworth MB, Pennell A, Phillips M, Vilar FJ. Managing hepatitis B/HIV co-infected: adding entecavir to truvada (tenofovir disoproxil/emtricitabine) experienced patients. AIDS 2011;25:1051-6.

Rosenthal E, Roussillon C, Salmon-Céron D, et al. Liver-related deaths in HIV-infected patients between 1995 and 2010 in France: the Mortavic 2010 study in collaboration with the Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA (ANRS) EN 20 Mortalité 2010 survey. HIV Med. 2014. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12204.

Sax PE, Wohl D, Yin MT, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, coformulated with elvitegravir, cobicistat, and emtricitabine, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: two randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet. 2015;385(9987):2606-15.

Schmutz G, Nelson M, Lutz T, et al. Combination of tenofovir and lamivudine versus tenofovir after lamivudine failure for therapy of hepatitis B in HIV-coinfection. AIDS 2006;20:1951-4.

Shepard CW, Simard EP, Finelli L, Fiore AE, Bell BP. Hepatitis B virus infection: epidemiology and vaccination. Epidemiol, et al. Entecavir therapy for lamivudine-refractory chronic hepatitis B: improved virologic, biochemical, and serology outcomes through 96 weeks. Hepatology 2008;48:99-108.

Snow-Lampart A, Chappell B, Curtis M, et al. No resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate detected after up to 144 weeks of therapy in patients monoinfected with chronic hepatitis B virus. Hepatology 2011;53:763-73.

Soriano V, Puoti M, Bonacini M. Care of patients with chronic hepatitis B and HIV co-infection: recommendations from an HIV-HBV international panel. AIDS 2005;19:221-240.

Soriano V, Mocroft A, Peters L, et al. Predictors of hepatitis B virus genotype and viraemia in HIV-infected patients with chronic hepatitis B in Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65:548-55.

Tateo M, Roque-Afonso AM, Antonini TM, et al. Long-term follow-up of liver transplanted HIV/hepatitis B virus coinfected patients: perfect control of hepatitis B virus replication and absence of mitochondrial toxicity. AIDS 2009;23:1069-76.

Thibault V, Stitou H, Desire N, Valantin MA, Tubiana R, Katlama C. Six-year follow-up of hepatitis B surface antigen concentrations in tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treated HIV-HBV-coinfected patients. Antivir Ther 2011;16:199-205.

Thornton A; Jose S, Bhagani S et al. Hepatitis V, hepatitis C, and mortality among HIV positive individuals.AIDS 2017 (18):2525-2532.

Van Bömmel F, Wünsche T, Mauss S, et al. Comparison of adefovir and tenofovir in the treatment of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology 2004;40:1421-5.

Van Bömmel F, de Man RA, Wedemeyer H, et al. Long-term efficacy of tenofovir monotherapy for hepatitis B virus-monoinfected patients after failure of nucleoside/nucleotide analogues. Hepatology 2010;51:73-80.

Van Bremen K, Hoffmann C, Mauss S et al.Obstacles to HBV functional cure: Late presentation and ist impact on HBV seroconversio in HIV/HBV coinfection. Liver Int. 2020; 12:2978-2981.

Wandeler G, Mauron E, Atkinson A et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in HIV/HBV-coinfected patients on tenofovir therapy: Relevance for screening strategies. J Hepatol. 2019. 71(2):274-280

World Health Organization. Global progress report on HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027077.